Educational Infrastructure

Few schools are set up to allow Sally and Max to carry out the work pictured in their Day in the Life. They lack the technical infrastructure that made such activity possible; but more importantly, they have not developed the educational infrastructure that Sally and Max need. This includes the content of the curriculum, its materials, coordination, and assessment devices; the class scheduling and student grouping practices; the revised teaching methods and varied roles for the teacher; and the full integration of all of these with networked digital technologies. This chapter describes the nature of this educational infrastructure necessary to Education 3.0, and how it might be built.

Curriculum

The course of study for Education 3.0 is different from the curriculum in 2.0. This new curriculum:

- includes many skills and concepts not included in the old curriculum;

- leaves out some of the items covered in the old curriculum;

- is closely coordinated across subjects and between teachers;

- is available to students, managed, and tracked 100% online;

- requires the use of many technologies, including networked mobile devices.

- is confronted by students along some very different paths.

Remember Sally's Day in the Life. While she ended up learning much of the same math, science, and literature as she would have under Education 2.0, she added to that many new skills in problem-solving and analysis. And while she no longer spends much time learning to factor fourth-order polynomials, she spent quality time with statistical sampling. The content of the curriculum in Education 3.0 reflects the kinds of knowledge and skill she's more likely to need in her 21st century.

Just about every topic Sally encountered in her day was connected directly to another subject area. Reading Thoreau's Walden while researching a local water-quality issue was not coincidental. Neither was the juxtaposition of statistics in math with water analysis in chemistry. The curriculum crafters for H.S. 21+ meticulously designed a combination of group problems and formal lessons that covered all the bases and linked them with a synchronicity and complementarity far beyond anything we see in Education 2.0.

Such a curriculum requires nimble accessibility, sequencing, and scheduling, so that it can shift as necessary. Therefore it's all online, where it's easy for the teachers to find what they need, re-order the problems and lessons, and update as they go along. And easy for the students to access from anywhere, at any time, from any of the many networked information devices they use. Because it's online, it's easy to find just the lesson you need to solve the problem at hand; it requires no extra work on the part of the faculty to keep track of who is working on what, for how long, and with what results. We'll see how important this is later in this chapter when we consider the importance of student assessment.

It's hard to find a printed textbook or reference book in Education 3.0. But it's easy to find the course of study -- just look on any of the computers, iPods, or other devices on the desks and in the pockets of the students and the faculty. A printed book does not keep track of who is reading what page, or how well they do on the end-of-chapter quiz. Nor can it help a struggling student to decode and pronounce an unknown word, or link a complex phrase to a visual reference, as the digital books did for Max. The online curriculum is essential to the efficiency and resiliency of student work in Education 3.0.

In addition to these computing, communication, and display devices are the data capture devices that the curriculum relies on. The data probe Sally used in the chemistry lab, the digital video camera her colleagues took to the bridge, even the violin that played the Bach riffs, formed integral aspects of the curriculum. These technologies enable the curriculum to interact directly with the facts on the ground, or under the water.

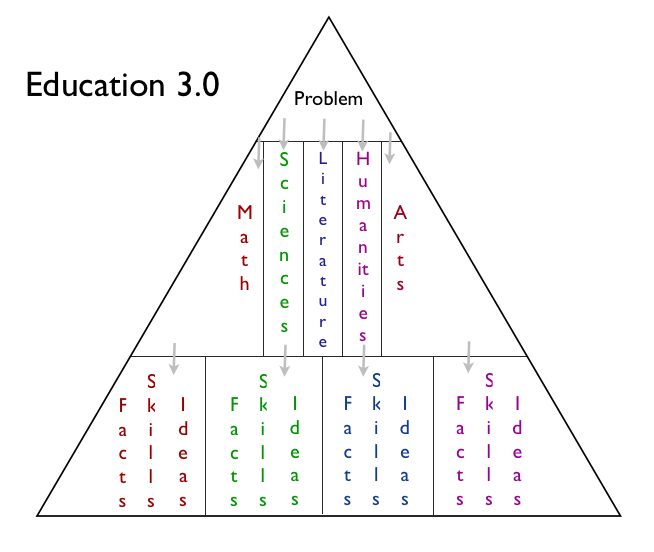

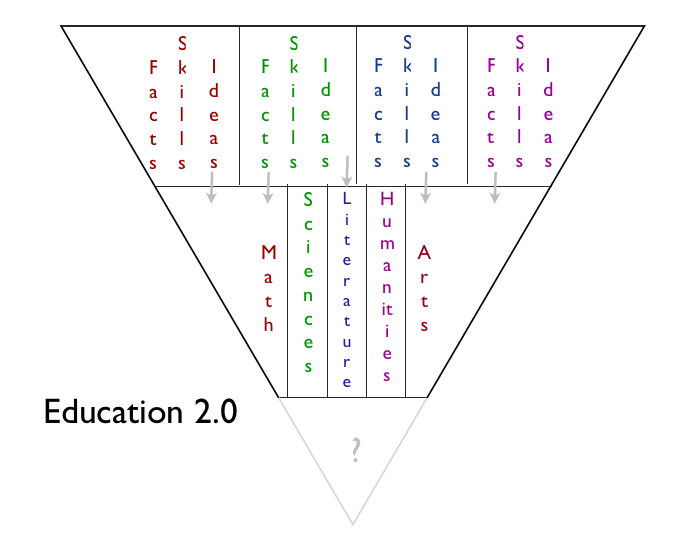

A good way to understand the difference between the curricula of Education 2.0 and 3.0 is to invert the pyramid. Think of it as a difference in where the curriculum starts.

In Education 3.0, the jumping-off point for study is a carefully-crafted, worthwhile, interdisciplinary problem -- a demand for students to apply many ideas and skills to a task at hand. Students start from the problem, which forms the tip of the pyramid. As they work through the problem, they are forced to work their way down to the rich depths of the pyramid, to learn the facts and conc pets and skills they need to solve it. The problem seems pointed and focused, but underneath it lies an array of content that must be brought to bear in its solution.

In Education 2.0, students begin at the fat end of the pyramid, absorbing (we hope) a mass of facts, concepts, and skills that may some day be applied to a worthwhile problem. Should they emerge from the wide mass of the structure, and survive the descent to the point, they may be asked to apply what they have learned to a focused problem. But they seldom get this far.

In fact in both eras of education the curriculum is formed of a myriad of pyramids. In Education 3.0, they are defined by the problems at their tips, with their bases made up of blocks from many different subject areas. In Education 2.0, the pyramids are defined by subject, all the math blocks in one, the literature blocks in another, many short and tipless, lacking a unifying focus.

The net volume of both sets of pyramids is about equal, and consist for the most part of the same blocks. But the architecture is very different.

Grouping and Scheduling

K-12 schooling in the Education 2.0 mode is wonderfully consistent in its grouping and scheduling of students and teachers. With few exceptions, a group of 25 students works in a room with a single teacher for sessions of a bit less than an hour, six or seven of times a day. What's the reason for this? Is this the best way to accomplish our objectives?

In Education 3.0, students find themselves working at times in a small group of five or six, at other times in a room with 25 of their peers, and often in a large group. The size of the group depends on what needs to be done. The work at hand may take 15 minutes, or a half-hour, or two hours. The time allotted depends on what needs to be done. The curriculum crafters designed the size and duration of the groups to fit the task at hand, and to take advantage of the basic human needs for variety and community.

So we found Sally in the library for a ten-minute huddle with her five project teammates, then in the big lecture hall for a 60-minute demonstration from the online scientific expert to 150, then in the math classroom for a half-hour discussion with 25 others. And we found Max sometimes alone, sometimes with a teacher in a small group, sometimes with a classful.

Some of their time was scheduled and directed for them, but some was allotted for self-directed activity. This self-direction is an important goal of the program; students earn more self-directed time as they work their way through their school careers. Sally enjoys much more freedom than her Education 2.0 counterparts, but this was earned gradually. And at the same time, Sally is more closely watched. All her time, every minute of the day, was effectively monitored by the communication devices she carried with her. The system knew where all the students were and what they were doing at all times. Remember how Mr. Bacon was warned when several of his students wandered off-campus to the bridge to plant their data probe. And Max's teacher gets a daily online report of the vocabulary words he is struggling with -- with a copy to his parents. Time and activity, seemingly more open and loose, is in fact logged and tracked more closely in Education 3.0.

The development of self-direction is taken seriously in Education 3.0. We will see later in this chapter, in the section on the student's role, how important it is to take advantage of students' growing needs for self-identity, self-direction, and personal industry that often given short shrift in Education 2.0. Capitalizing on the energy and industry of youth is a key component of Education 3.0.

The varied scheduling and grouping also enables a different role for the teacher, and permits a wider array of teaching and learning methods.

Teaching Methods

The inversion of the pyramid described above calls forth some very different approaches to teaching. In the Education 2.0 pyramid, students visit the levels of each subject-pyramid block-by-block and row-by-row, beginning at the wide end. Seldom does their path form a logical sequence; seldom does it detour to a neighboring pyramid. At each block, the general method is the same:

- Present the content

- Discuss or practice it

- See if you've learned it

- Put it aside in your mind

- Go on to the next block.

And the specific techniques of teaching naturally limit themselves to this format. Teachers learn to present content, lead a discussion, and administer tests. These become the standard methods of instruction in the schools. Teaching centers around the lesson, a relatively short session in which a distinct block of content is set forth, exercised, and tested. In this routine, students often find themselves performing the identical task as the person next to them. They seldom need to use resources from outside of the school. And there is little advantage offered by networked information technologies.

The general method of Education 3.0 looks more like this:

- Confront a worthwhile problem.

- Seek out ideas, facts, and skills that might help solve it.

- Gather, learn, and practice those ideas and skills.

- Apply them to the problem.

- Publish a solution.

The techniques for teaching in this context are quite different. Teachers spend their time articulating problems, pointing students to useful content, helping them learn and apply new ideas and skills, and teaching them how to publish their solutions. Teaching centers around the relatively long problem-solving process, in which an issue is introduced, attacked, and its solution published.

In this routine, students seldom find themselves performing the same task as the person next to them. They often rely on resources far beyond the walls of the school. And they simply could not get the work done without the help of digital networked information tools.

The general methods and routines of teaching and learning in Education 3.0 are more like the methods and routines of the modern laboratory and the workplace, than they are like the school of Education 2.0. The way that time is used, the responsibility expected of the students, they motivation for the work, are less like school and more like work.

Students spend less time on paper and pencil tasks, and more time on computer-based tasks.

Students seldom perform the exact same task as the student next to them.

Students learn as much outside of the school building and day as they do inside.

Learning relies on real-world computer and network tools, the same ones used in the world of research and business.

Assignments require collaboration with other students, extra rewards for creative analysis, and the expectation of innovative solutions.

Teacher's Role

All faculty are expected to teach collaboration skills and problem-solving techniques.

Teachers coach a small group of students through a problem-solving exercise and then grade them on it.

Teachers coordinate their every assignment with their peers in other subjects.

Outside experts

Student's Role

Take responsibility for their own learning.

Building a portfolio.

Pull, not push.

Assessment

Of the full range of expectations

An array of methods, to best fit: test, performance, product

Portfolio structured and required

Frequent assessment, much of it online

| Back | Next | |

copyright © James G. Lengel 2010 |